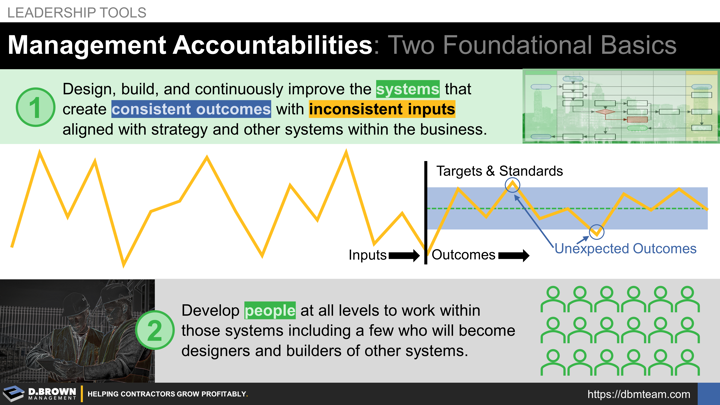

Keeping It Simple: Managers and Management Systems have two foundational accountabilities.

- Design, build, and continuously improve the systems that create consistent outcomes with inconsistent inputs aligned with strategy and other systems within the business.

- Develop people at all levels to work within those systems including a few who will become designers and builders of other systems as the contractor continues to evolve. This is what "Succession at All Levels" means on the Contractor Scoreboard.

The actual execution of that gets far more complex, especially as contractors navigate different stages of growth.

Starting at the highest levels, leadership makes choices about strategy which includes some high-level targets and a basic model of the resources and metrics required to get there. At the company level, that model may include key things like:

- Target revenue by market sector.

- Size of the opportunity pipeline.

- Ratio of opportunities identified, projects pursued, and projects won.

- Target gross margin by market sector, project type, delivery method, and size.

- Average cost and hours required to pursue an opportunity including business development, preconstruction, cost estimating, and proposal development.

That only defines one aspect of the business - securing the work, but is enough to provide an example. A business model tied to strategy would be complete down to the critical assumptions that must be true for all parts of the Contractor Business Model relevant to the current and next stage of growth.

Making these strategic decisions and developing this high-level business model is the role of top leadership as it often involves change.

These critical assumptions form the highest levels of standards for the contractor. The "Business of Building" is about designing the systems that will most consistently achieve these standards within a tolerance range for all areas of the business. This is where management starts to break these down into more specific assumptions and metrics for their functional area.

The simplest example is to look at the cost estimation function. The manager who is accountable for this function must develop metrics all the way down to labor units to install various types of construction materials in different conditions that are aligned with current operational capabilities.

The key deliverable from the cost estimation function is accurate costs, quantities, and hours given the schedule and conditions.

Beyond the estimating database, they must also develop systems that make the cost estimating process efficient and consistent which will include workflows, standard procedures, technology tools, and routine checks for quality control (QC - right outcomes) and quality assurance (QA - right process).

For everything to operate effectively, the system must include a way to integrate feedback from operations on performance that is outside the expected range either better or worse. The accountability for designing and managing that system that integrates operational feedback to cost estimating must be from a higher-level manager who is accountable for both project execution and cost estimating.

Remember that these are just examples to start to see how standards and systems are integrated up, down, and across a construction business.

Just that level of integration between cost estimation and operational integration is incredibly difficult. Now we have to add another dimension to tie everything back to the strategy and higher-level standards we started with. Assuming we have this alignment, we now have a couple other very big things to align on:

- Will the competitive market allow us to sell the projects at a price that meets or exceeds the standards for gross margin?

- At this level of pricing and our average rate of winning these projects, are we seeing enough opportunities in our pipeline to achieve our strategic targets?

This is where the feedback loop comes in where systems and standards are continually being adjusted by management. This is not the same as subjective deviation in the moment. This is part of the Plan>Do>Check>Act (PDCA) continuous improvement process which starts with standards.

You can take this accountability for meeting the standards all the way down to a Crew Leader responsible for a few people and performing a task on the project. Assuming their manager (Foreman or Super) defined the task effectively and made sure the six pillars of productivity were met, the Crew Leader's biggest variables will likely be:

- The people on their crew including varied capabilities, behaviors, and outside conditions that can impact their work.

- Gaps or conflicts in information - even the best laid plans can have errors or need more interpretation.

- Jobsite conditions in the work area changing throughout the day even though they seemed clear at the start of the task.

- Tools or equipment breaking down.

The company may have specific installation standards for the task they are doing, have provided prefabricated materials, or material kits. The company may have also defined standard procedures for escalation of certain categories of problems the Crew Leader may encounter.

Working within those systems, the Crew Leader has the direct responsibility to complete the task safely, at the quality level required, and at the production rate that was budgeted. In the perfect world, it would happen like this every time. In the real world, there are a variety of "Unexpected Outcomes" which are either higher or lower than the standard and tolerance levels. For example, if the task performance expectation is +/- 5% for tasks or groups of tasks over 100 hours, then you would dig further into those unexpected outcomes to make adjustments to the system, the standard, the manager, or the people.

The only thing that changes with progression in levels of management are the decision rights over a larger percentage of the system. The Crew Leader has most everything defined for them and are responsible for a few variables then escalating problems. That manager that must align cost estimating with operational execution and the market has very little defined for them with a lot more variables and the timing from action-to-feedback occurring over a much longer time span. Learn more about coping with the complexity of longer time spans with Stratified Systems Theory (SST).

While managers are delivering the outcomes, they must be focused on the development of people along the way. If the system design and management hasn't accounted for that then the system isn't scalable or sustainable, and neither is the contractor.

Examples of building developing into a system include deconstructing certain job roles so that people with less experience can gain experience by doing parts of a bigger role. For example, a Field Engineer can learn to be a Superintendent by taking on some of the tasks a Superintendent or Foreman would typically do. This allows more capacity for the scarce resources of experienced Superintendents while allowing the Field Engineer to learn while being productive.

As a closing note, we see more contractors struggle due to lack of consistent management than poor strategies, difficult customers, or front-line workforce. Management is both a set of skills and a routine process. This requires training, discipline, and management from whoever they are accountable to.