The fastest way to close the gap on the construction industry's talent shortage from craft through management is deliberate practice. This is far, far different from simply having "experience" based on quantity of repetition or time spent on the job.

Generic Example

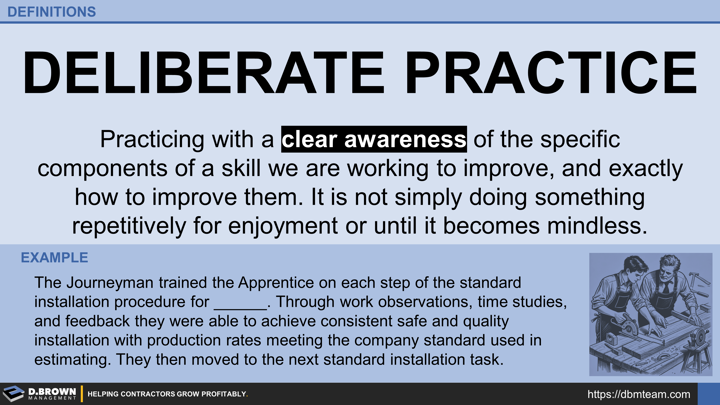

The Journeyman trained the Apprentice on each step of the standard installation procedure for ______. Through work observations, time studies, and feedback they were able to achieve consistent safe and quality installation with production rates meeting the company standard used in estimating. They then moved to the next standard installation task.

Note that this requires the Contractor and the Journey-Level person assigned to teach the Apprentice to have clear standards for installation—even if they are not thoroughly documented.

Learning More: Four books that will help you more deeply understand the concept and application of both self-development and development of your team.

The Little Book of Talent (Daniel Coyle)

Talent is Overrated (Geoff Colvin)

The Talent Code (Daniel Coyle)

Broader Application Example (Beyond Construction and Craft)

Geoff Colvin provides a great example of how deliberate practice was used to rapidly develop new hires and dramatically improve their outcomes. He includes the most important details, such as the intense time commitment required of management at the beginning and the fact that everyone complained. 3-Minute Video

Construction Craft Example (David's Early History)

Learning more about conduit bending and route planning in two painful weeks than most gain in years.

Example written first-person from David's perspective using some language specific to the electrical trade. The principles are applicable to all trades and job roles.

Some of my earliest experience running conduit was with rigid in an industrial facility. My Journeyman was Chuck. He explained that many people slow down with rigid conduit but if you plan things out well, you can be nearly as fast with rigid as with EMT. His rules were simple but very, very hard—at first.

- You have to go into the room and plan the whole room at once on a notepad.

- You only get to go to the threader one time—walking is expensive.

- No unrequired 3-piece fittings—they are expensive.

He checked me at every step of the way, starting with my notes.

He asked questions to challenge me on routing and sequence of installation, being pretty harsh if I planned something that wouldn't actually work when threading it together or misused the expensive 3-piece fittings. I was very frustrated at 17 years old, wanting to "hurry up" and get started cutting and threading conduit.

He watched every move I made when it came to gathering materials, cutting them, threading them, and moving them to the room for installation. His feedback seemed like nitpicking micromanagement, but it was really just very deliberate coaching—what Daniel Coyle later called "GPS Feedback."

The observing and constant feedback continued as I was installing the conduit in the room.

The first day went very slow. I started picking up speed by the third and fourth rooms.

Sometimes, he deliberately "allowed" me to make mistakes and then showed how I could have prevented them, along with how much time and material I wasted.

The first few days he was barely productive himself.

By the last couple days of the week, he was back to being productive and "racing" me to make the learning experience fun. During that week, I never got as fast as him, but I did get a lot faster as an apprentice than many of the others on the job.

That intentionality with rigid made EMT go in with ease—it cut like butter, and routing was far easier without the need to thread things together. I minimized ladder and lift movement.

Few months later on another job, Chuck set me up for a second great learning experience, which was fabricating about 2,000 standard bends. Today, that would likely be done in a prefab shop by a machine. I got to experience high repetitions of five basic bends. Several times per day he would stop by and observe me for about 15 minutes, giving me very specific feedback. This included timing me (production) and checking for quality (degrees and inches).

The lessons from this are a three-part plan to mitigate the talent shortage:

- Start as early as possible—inspiring kids in middle-school and exposing them to tools and the industry is where it all begins.

- Deliberate Practice starts with pairing people with others who will coach them, like what Chuck did for David.

- Specialization of job roles, even on the jobsite, is critical. For example, it may take years to develop the general range of Journey-Level skills but only weeks to get to Journey-Level capabilities for a specific task like conduit running.