A look at the 2023 ENR Top 400

- The ENR Top 400 Largest General Contractors accounted for $460B worth of work in the US, which is about 26% of the $1.8B in total US construction spending for 2022.

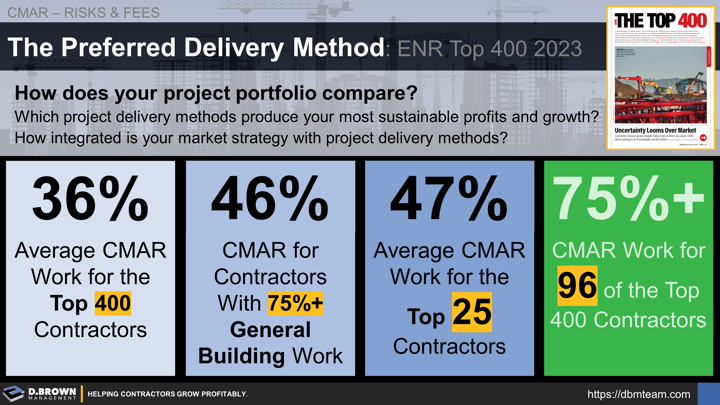

- The Top 400 Largest GCs used CMAR on 36% of their projects overall.

- The Top 25 Largest of those contractors used CMAR 47% of the time on $1.65B of projects built in the United States.

- Those with 75% or more of their work classified as general building work used CMAR 46% of the time.

- 96 of the Top 400 used CMAR over 75% of the time.

- These 400 contractors represent only 4.5% of the total GCs in the US with revenues over $10M.

Whether you are a General Contractor or Specialty Contractor, you can build a competitive advantage and extend the time horizon of your work conversion cycle, lower risk, and combat the talent shortage by improving your CMAR delivery capabilities.

Project Delivery Methods that align with your customers are part of your strategic market choices.

Study trends in the market and different industry sectors - both those you are in, and those that you may want to build capabilities in.

Get to know the project owners to understand what matters most to them. A great place to start for a general overview is:

- FMI Partner Jay Bowman and Consulting President Scott Winstead discuss their 2023 forecast and economic assessment of the construction market. (Audible Link - 45min). Notable takeaways are:

- Geographic concentration

- Increase in projects $1B+

- The value of relationships when markets decline.

- FMI Senior Consultant Tracey Smith talks with Randy Leopold who oversees construction for UC San Diego managing billions of dollars of projects. (Audible Link - 35min). Notable takeaways include:

- The value of preconstruction capabilities including in the earliest stages while projects are being considered at the conceptual stage.

- What they value in contractors as a project owner.

- How they get input from other project owners and contractors about the best project delivery methods to use. CMAR is their delivery method of choice.

A Brief History of Project Delivery Methods and Supply Chain Management

To understand why CMAR is currently the preferred method by many large project owners and the contractors that build for them, it is important to look back at the history of project delivery in construction. For a project owner, construction is just one of the many things they purchase to serve their customers so the trends in project delivery are really about the trends in supply chain management.

We are using auto manufacturing as the supply chain example, but similar trends were happening throughout all industries.

Early 1900s

- Cost-plus Contracts: In the early part of the 20th century, many industrial projects, particularly large ones, were executed using cost-plus contracts. These contracts reimbursed the contractor for the actual costs incurred plus an additional amount to account for overhead and profit. Such contracts were favored because they provided a degree of flexibility in situations where the scope of the project wasn't entirely clear at the outset.

- Integrated Firms: Many large industrial companies operated with integrated engineering and construction divisions. These entities could handle everything from design to commissioning, reminiscent of the "master builder" approach but on an industrial scale.

- Ford's Model T Era: Henry Ford's vision was to control the entire production process. The River Rouge Complex, operational in the 1920s, epitomized this. From raw materials to the finished product, everything was under Ford's control. The iron ore mined from Ford's own mines was transformed into steel and then into cars within the same complex. This approach minimized dependence on suppliers.

Mid 1900s

- Move Toward Design-Bid-Build (DBB): Post World War II, as the scale of industrialization grew, there was a trend toward more specialization. Design-Bid-Build began to gain popularity even in the industrial sector. Specialized design firms would handle the design phase, and then the construction phase would be tendered out to contractors, leading to clearer demarcations but also more hand-offs between project stages.

- Economic Pressures: The oil crises and economic pressures of the 1970s made cost predictability more important. Fixed-price contracts gained favor, pushing a move away from cost-plus models.

- GM vs. Ford: While Ford championed vertical integration, General Motors (GM) took a different approach. Alfred Sloan, GM's CEO, believed in a decentralized approach. GM relied more on a network of suppliers than Ford did, setting the stage for the industry's future reliance on external suppliers.

- Post-WWII Boom: After World War II, there was a massive demand for cars. The car manufacturers began to focus on their core competency - designing and assembling cars - while relying on a network of suppliers for parts. This trend was driven by economies of scale, technological complexity, and the benefits of specialization.

Late 1900s through Today

- Rise of EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction): By the 1980s and 1990s, the EPC contracting model began to gain traction in the industrial sector. Under EPC contracts, one entity is responsible for all stages of project delivery. This reintegrated approach ensured that design and construction were coordinated, and owners had a single point of responsibility.

- Shift to CMAR and IPD: Learning from the pitfalls of overly compartmentalized project delivery, the industrial sector, similar to other sectors, started exploring CMAR and IPD in the late 20th and early 21st century. These models emphasized collaboration, risk-sharing, and early involvement of construction expertise during the design phase.

- Lean Supply Chain: Inspired by Japanese automakers, U.S. car manufacturers adopted lean supply chain practices, minimizing inventory costs. However, this meant that disruptions in the supply chain could halt production. This influence started with Japanese competition in the 1970s and 1980s with the first major knowledge transfer beginning in 1983 with the Toyota-GM Joint Venture, New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI).

Note that many of these problems were caused because they were applying only part of the lean philosophy that Toyota used. Toyota's philosophy and approach was on helping all their first and second tier suppliers adopt lean methods and more tightly integrate into the whole process of designing, selling, manufacturing, and servicing vehicles. You can see the same challenges as the construction industry works to adopt these tools and is only focused on part of the process.

The potential use of lean production methods for construction was introduced in the 1990s starting with a paper titled "Application of the New Production Philosophy to Construction" from 1992 then the founding of the Lean Construction Institute in 1997 with growing acceptance and implementation in the 2000s and widespread recognition of both the benefits and challenges in the 2010s through today.

Throughout the history of construction project delivery, there's been a pendulum swing between integrated and specialized approaches. Lessons from project challenges coupled with changing economic and technological landscapes have driven the evolution of delivery methods, always in pursuit of better project outcomes, cost efficiencies, and risk mitigation.